Humanity first: Olivetti's blueprint for trustworthy AI

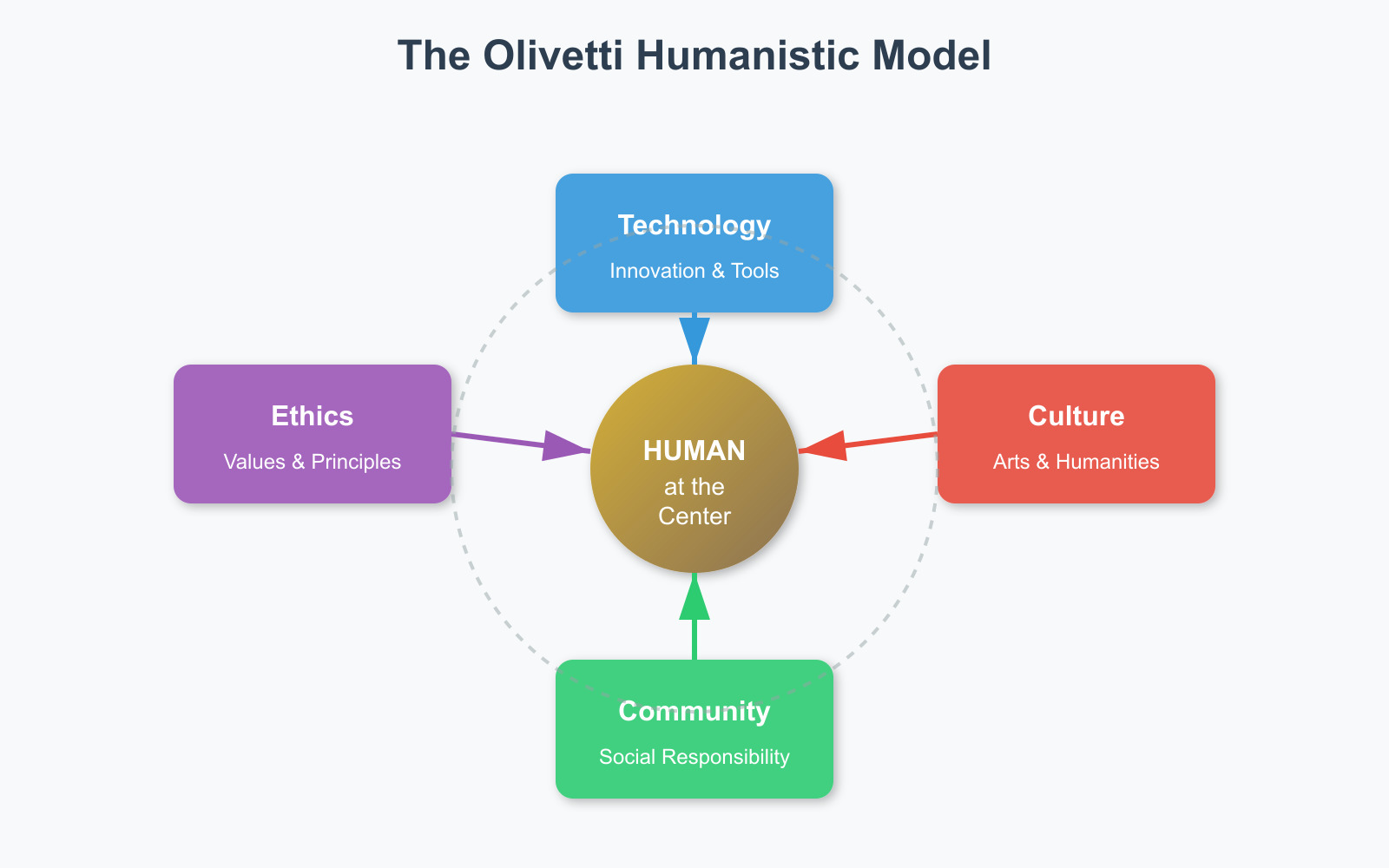

Long before neural networks started drafting memos and marketing copy, Adriano Olivetti proved that advanced technology only thrives when it is anchored to humanistic intent. His factories in Ivrea blended design, culture, architecture, and social welfare into a single philosophy: machines should amplify dignity, not diminish it. That insight feels urgent again as AI systems quietly reshape how we work, deliberate, and learn.

Generative AI has reignited a fundamental debate: who gets to define progress when algorithms mediate our choices? The hum of community-focused industry that Olivetti championed offers a counterpoint to opaque models trained on inscrutable datasets. His blueprint reminds us that leadership requires rhetorical agility, ethical discernment, and civic imagination, not just computational power.

The topic is personal: I have spent years mining Olivetti’s archives and even distilled his approach in a dedicated piece on human-centric team management. Revisiting those lessons now reveals how effortlessly they map onto boardroom discussions about AI governance and responsible deployment.

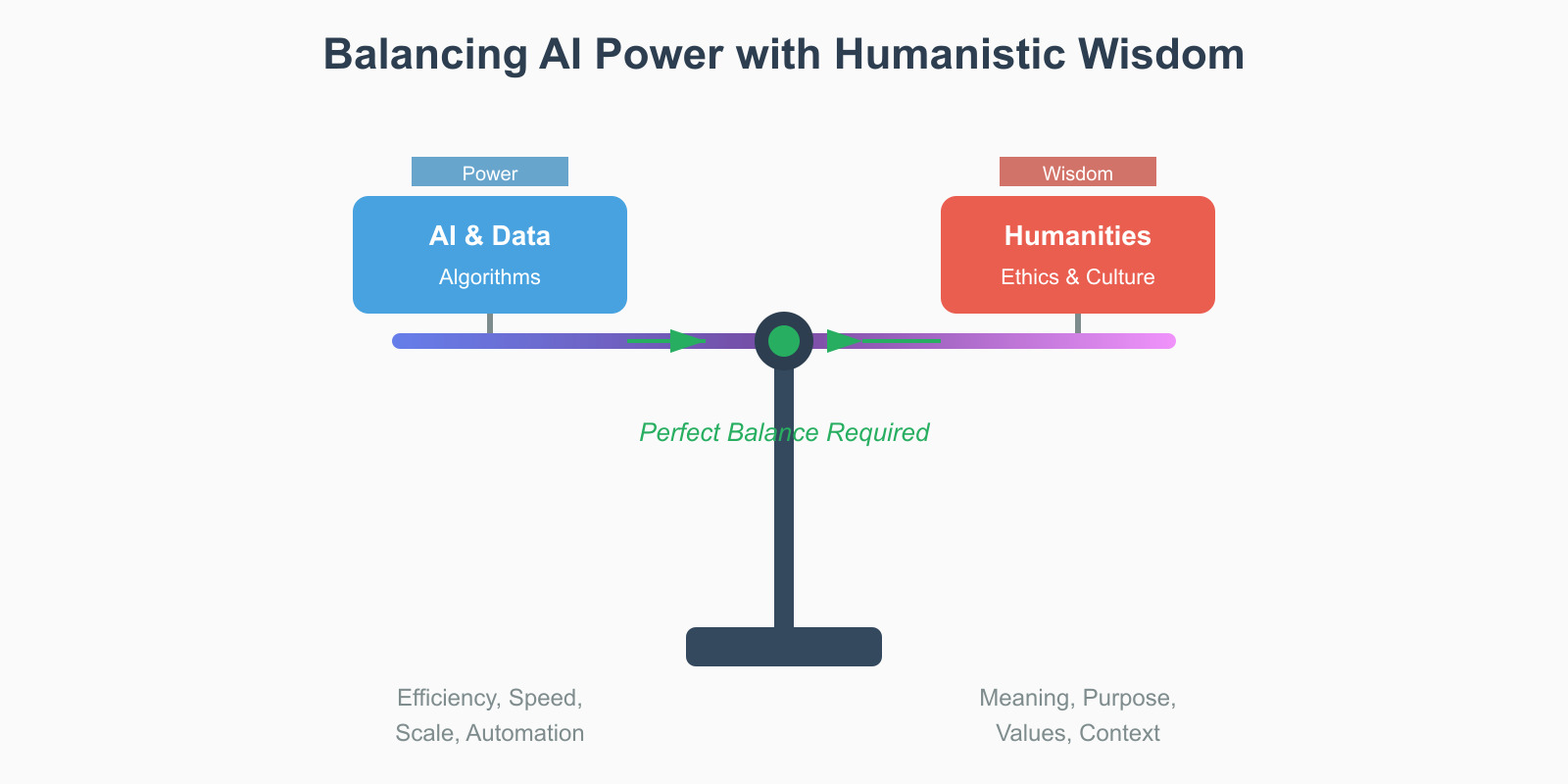

Mediterranean humanism, with its blend of classical rhetoric, social responsibility, and measured innovation, equips us to interrogate AI systems instead of surrendering to them. When models can fabricate prose, imagery, or strategy in seconds, the real differentiator becomes our ability to judge, contextualize, and humanize those outputs. That is precisely where Olivetti’s cultural infrastructure becomes a guide for today’s leaders.

The Mediterranean tradition and technological humanism

Olivetti’s approach to industry was revolutionary precisely because it refused to separate technological advancement from humanistic concerns. In the factories of Ivrea, workers weren’t just production units but participants in a broader social experiment. The company invested heavily in housing, education, cultural programs, and community infrastructure, recognizing that human creativity and productivity emerged from holistic wellbeing rather than narrow optimization metrics. This philosophy drew directly from Mediterranean humanism, which viewed knowledge as integrated and inseparable from ethics and social responsibility.

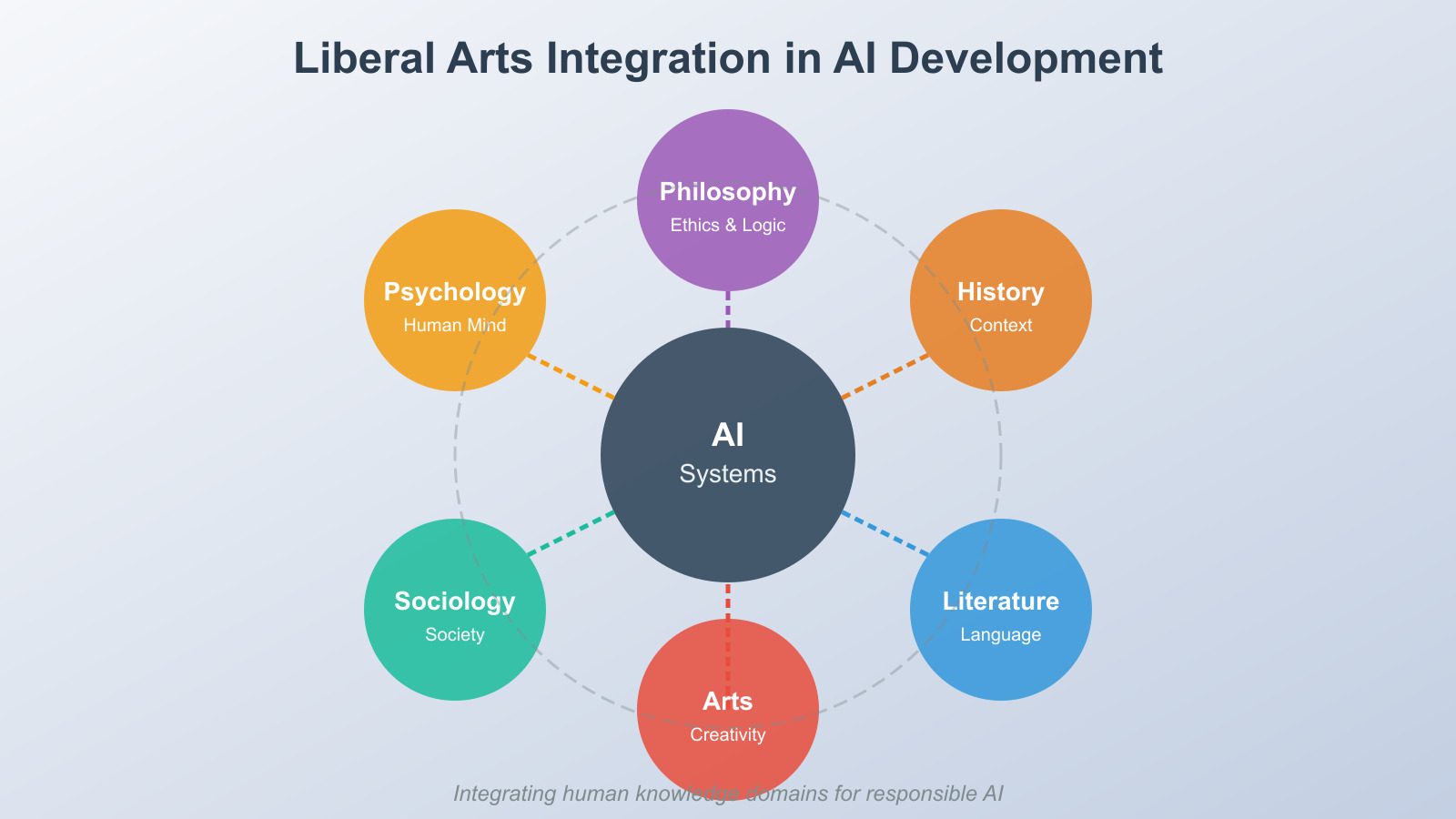

The liberal arts tradition that informed Olivetti’s vision encompasses rhetoric, grammar, logic, arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy, disciplines that trained students not in specific vocational skills but in the capacity for reasoned judgment across domains. This educational model produced individuals capable of recognizing patterns, questioning assumptions, and synthesizing diverse knowledge sources, exactly the competencies required when dealing with opaque algorithmic systems that increasingly shape public and private life. The contrast with contemporary technical education, which often emphasizes narrow specialization over broad understanding, could hardly be starker.

Modern AI development frequently prioritizes technical performance metrics like accuracy, speed, and scalability while treating ethical and social considerations as secondary constraints. This inverted priority structure would have been incomprehensible to Olivetti, whose business model explicitly subordinated profit maximization to human wellbeing and community development. The Mediterranean approach recognized that technology exists within social contexts, shaped by and shaping human relationships, values, and institutions. Separating technical development from these contexts produces systems that, however sophisticated technically, may undermine the very human capacities they purport to enhance.

The opacity problem in contemporary AI systems

Generative AI represents a qualitative shift in technological opacity. Traditional software systems, however complex, operated according to rules that could in principle be understood and audited. Contemporary deep learning models, by contrast, develop internal representations and decision processes that remain fundamentally opaque even to their creators. When a large language model generates text or an image generation system produces visual content, the specific computational pathways producing those outputs resist straightforward interpretation. This technical opacity creates profound challenges for accountability, oversight, and responsible deployment.

The concentration of AI capabilities within a small number of technology corporations exacerbates this opacity through what might be termed institutional opacity. The proprietary nature of training data, model architectures, and deployment strategies means that critical decisions affecting millions of users occur behind corporate barriers inaccessible to public scrutiny. When OpenAI, Google, or Anthropic makes choices about content moderation, bias mitigation, or capability limitations, these decisions shape public discourse and knowledge production with minimal democratic input or accountability. The power asymmetry between AI developers and AI users grows as systems become more capable and more central to social functioning.

This dual opacity, technical and institutional, creates conditions where algorithmic systems operate as what Olivetti might have recognized as authoritarian technologies, systems that demand compliance without offering comprehension. Users interact with AI outputs without understanding how those outputs were generated, what data informed them, what biases they might contain, or what interests they serve. The rhetorical competencies emphasized in classical education, the ability to analyze arguments, identify unstated assumptions, and evaluate evidence, become essential tools for navigating this landscape. Without these skills, individuals risk becoming passive consumers of algorithmic outputs rather than critical evaluators capable of independent judgment.

The challenge extends beyond individual users to institutions and societies. Democratic governance requires that citizens understand, at least broadly, the systems shaping collective life. When algorithmic systems mediate everything from credit decisions to medical diagnoses to content recommendations, public comprehension becomes a prerequisite for meaningful democratic participation. The humanistic tradition offers frameworks for cultivating this comprehension, not through technical training alone but through integrated education that connects technical capabilities to ethical implications, social contexts, and historical patterns.

Cultivating critical competencies for the AI era

The Olivetti model suggests that responding effectively to AI challenges requires more than technical expertise. It demands what we might call AI literacy, a multifaceted competency combining technical understanding, critical analysis, ethical reasoning, and historical perspective. This literacy doesn’t require everyone to become AI developers, any more than civic literacy requires everyone to become lawyers. Rather, it involves cultivating the capacity to ask informed questions, recognize limitations, and participate meaningfully in decisions about AI deployment and governance.

Rhetorical competence forms a crucial component of this literacy. Classical rhetoric taught students to analyze persuasive techniques, identify logical fallacies, and construct compelling arguments. These skills prove directly applicable to evaluating AI-generated content, which often appears authoritative while potentially containing errors, biases, or misleading framings. The ability to ask “who benefits from this framing?” or “what evidence supports this claim?” or “what alternatives exist?” represents practical applications of rhetorical training to algorithmic outputs. Critical thinking frameworks developed over centuries remain relevant precisely because they address perennial human challenges, distinguishing truth from falsehood, recognizing manipulation, and exercising independent judgment.

Historical perspective offers another essential competency. The challenges posed by AI aren’t entirely novel; they echo earlier technological transformations that disrupted established practices and power structures. The printing press, telegraph, radio, and internet each created new possibilities for communication while also enabling new forms of control, surveillance, and manipulation. Understanding these historical precedents helps contextualize AI developments, revealing patterns that might otherwise remain invisible. The Mediterranean humanistic tradition emphasized historical knowledge precisely because it cultivated wisdom, the capacity to recognize recurring patterns and apply lessons from past experiences to present challenges.

Ethical reasoning, always central to liberal arts education, becomes indispensable when dealing with technologies that make or inform consequential decisions. When AI systems recommend medical treatments, approve loans, screen job applications, or target advertisements, they operationalize ethical judgments about fairness, privacy, autonomy, and human dignity. Understanding the ethical frameworks underlying these judgments, whether utilitarian, deontological, virtue-based, or care-oriented, enables more informed evaluation of AI implementations. The question isn’t whether AI systems embody ethical positions but which positions they embody and whether those align with human values and social priorities.

Recovering humanistic leadership in technological development

Olivetti’s example demonstrates that integrating humanistic perspectives into technological development isn’t just philosophically desirable but practically achievable. His companies competed successfully in global markets while maintaining commitments to worker welfare, community development, and cultural enrichment. This success contradicted prevailing assumptions that humanistic values necessarily compromise competitive performance. Instead, Olivetti showed that treating workers as whole human beings with diverse needs and capabilities could enhance rather than hinder productivity and innovation. The integration of humanities and technology produced not just better working conditions but better products.

Contemporary AI development could benefit from similar integration. Rather than treating ethics boards as afterthoughts or public relations exercises, companies could embed humanistic expertise throughout development processes. Philosophers might contribute to conceptualizing fairness and transparency. Historians could provide context about previous technological transformations and their social consequences. Literary scholars might analyze how language models reproduce or challenge cultural assumptions. Sociologists could study how AI deployment affects communities and institutions. This multidisciplinary approach would slow development cycles but might also produce systems better aligned with human needs and social values.

The Olivetti model also emphasized democratic participation in technological decisions. Workers at Ivrea weren’t just consulted about working conditions; they actively shaped factory operations and community development. Translating this principle to AI governance suggests moving beyond expert-driven or corporate-controlled development toward more participatory models. Citizens affected by algorithmic systems should have meaningful input into their design, deployment, and oversight. This requires not just consultation but genuine power-sharing, acknowledging that those most affected by technologies often possess crucial knowledge about their impacts and implications that developers and executives lack.

Implementing such participatory approaches faces significant obstacles. Technical complexity creates genuine barriers to broad participation. Corporate interests resist transparency and accountability that might limit profitable but problematic applications. Regulatory frameworks lag behind technological capabilities. Yet these challenges aren’t insurmountable. The Mediterranean humanistic tradition never promised easy solutions but rather provided frameworks for thoughtful engagement with difficult questions. Olivetti succeeded not by ignoring market pressures or technical constraints but by refusing to treat them as overriding considerations that nullified other values.

Building technological systems worthy of human dignity

The ultimate question posed by generative AI and related technologies isn’t technical but philosophical: what kind of technological future do we want to inhabit? The Olivetti model insisted that technologies should serve human flourishing, defined not narrowly as efficiency or productivity but broadly as encompassing creativity, community, dignity, and meaning. This vision requires resisting technological determinism, the assumption that because something can be built, it must be built, or that technical capabilities automatically translate into social benefits.

The humanistic tradition cultivated precisely the capacities needed to resist such determinism: the ability to imagine alternatives, to question prevailing assumptions, to prioritize values over expedience, and to recognize that human purposes should guide technological development rather than being determined by it. These capacities don’t emerge automatically from technical education alone. They require exposure to philosophy, history, literature, arts, and social sciences, disciplines that explore fundamental questions about human nature, social organization, ethical reasoning, and the good life.

Adriano Olivetti demonstrated that businesses could embrace these broader purposes without sacrificing competitiveness or innovation. His companies thrived precisely because they treated workers as full human beings whose creativity, judgment, and commitment were cultivated through holistic support rather than narrowly extracted through optimized control. The lesson for AI development is clear: systems designed with genuine understanding of human needs, values, and contexts will likely serve us better than systems optimized purely for technical performance metrics defined by developers or shareholders.

The path forward requires recovering the wisdom of liberal arts education while adapting it to contemporary technological challenges. We need educational systems that cultivate both technical competence and humanistic judgment, producing graduates capable of building sophisticated AI systems and questioning whether those systems truly serve human welfare. We need companies that embed ethical reasoning and social responsibility throughout development processes rather than treating them as constraints to minimize. We need regulatory frameworks that empower meaningful democratic participation in technological governance. And we need cultural commitments to placing human dignity and flourishing at the center of technological progress.

Olivetti’s vision wasn’t utopian fantasy but demonstrated practice. The challenge facing our AI-saturated present is whether we possess the wisdom and courage to learn from his example, integrating technological capability with humanistic values to build systems worthy of the human dignity they should serve. The stakes couldn’t be higher. Without this integration, we risk creating powerful technologies that diminish rather than enhance human agency, community, and meaning. With it, we might yet realize technology’s promise to support rather than supplant human flourishing.