Italy’s 10% cyber incident problem

Why 10% is a national warning, not a trivia fact

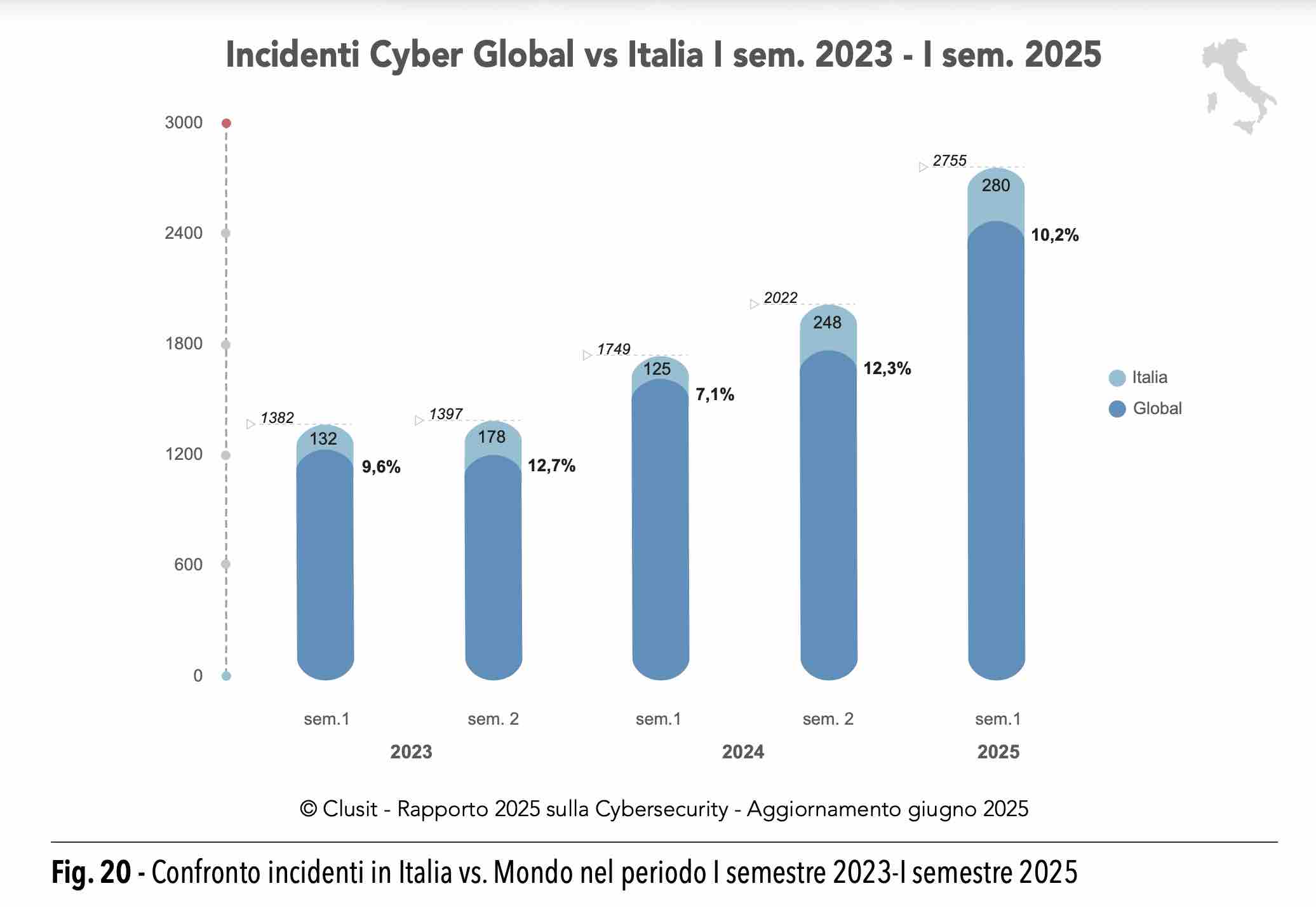

When a country that is not 10% of the world’s economy absorbs roughly 10% of the world’s publicly observed, high-impact cyber incidents, the figure is not a curiosity. It is a loud signal that attackers succeed here more often than they should. In Italy, the gap between intent and impact is the story: many places get probed, but too many Italian targets get hit hard enough to become incidents with operational, financial, or reputational damage.

That disproportionality is the uncomfortable message behind the 2025 snapshot discussed around the Clusit report, where the methodology focuses on incidents with tangible consequences rather than the endless background noise of attempted intrusions, and where voices such as Luca Bechelli have stressed how outsized the metric is versus Italy’s economic weight. The distinction matters because it points to effectiveness, not just volume. Disproportionate exposure is what happens when routine attacks keep finding weak seams, and when recovery is slower than the adversary’s learning curve.

The reflex response is often defensive, to argue about counting rules, or to hide behind the comforting ambiguity of “threat landscape.” But this is not a semantic debate. It is a competitiveness issue, an industrial continuity issue, and increasingly a public trust issue. If the metric feels abstract, imagine it as lost shifts, delayed shipments, frozen production lines, and emergency procurement done under pressure.

Why attackers keep winning in the Italian economy

The Italian target set is unusually tempting because it combines high-value activity with uneven security maturity. A large manufacturing base means a dense concentration of intellectual property, production data, and operational technology that is difficult to modernize without downtime. Logistics is a force multiplier: disrupting a transport node can ripple through an entire supply chain in hours. Public administration and defense, especially when services are digitized faster than governance can be rebuilt, remain attractive for disruption and visibility.

The ENISA threat landscape frames this reality in a way that resonates beyond national borders: ransomware, supply chain compromise, and credential abuse thrive where complex ecosystems meet incomplete fundamentals. In Rome and Milan, the problem is not a lack of awareness, it is the persistence of legacy constraints, fragmented ownership, and procurement cycles that treat cybersecurity as a product rather than a capability.

Hacktivism and DDoS campaigns add a distinctly political layer, where spectacle can be the goal and the operational side effects become collateral damage. Yet the most consequential incidents still tend to come from the predictable mix of malware, exploitation, and stolen credentials. The technical verbs are familiar. The outcome is not. The difference is the size of the attack surface, and the speed at which organizations can shrink it.

Why “inclusive” and “agile” slogans can make security worse

There is a corporate habit that deserves more scrutiny: the public embrace of inclusive and agile language, paired with day-to-day practices that punish candor and reward optics. Many organizations will publish values statements, sponsor diversity campaigns, and talk about empowerment, then run teams through chronically understaffed rotations, silent on-call expectations, and decision-making that is centralized at the first sign of risk. That is not agility, it is fragility with better branding.

Security suffers first because it depends on fast truth-telling. Vulnerabilities are discovered by people who must feel safe raising their hand. Incidents are contained by teams that must be able to escalate without fear of blame. When “agile” is used as a pretext for perpetual urgency, and “inclusive” becomes a marketing badge rather than psychological safety, problems go underground. Patch delays get rationalized. Exceptions become permanent. Documentation becomes optional. The outcome is security debt that grows silently until it becomes a headline.

This is where frameworks can be misread. The NIST cybersecurity framework is not a certificate to hang on a wall, it is a disciplined way to build repeatable outcomes across identify, protect, detect, respond, and recover. But discipline is cultural before it is technical, and no tool will compensate for a workplace where the real risk story lives in private chats while the official one is sanitized in Jira.

What needs to change, and why it starts on Monday

National strategy matters, but it does not patch a VPN appliance at 2 a.m., nor does it redesign an access model that has drifted into chaos. The gap closes when organizations treat resilience as a measurable operating capability, tied to budgets, incentives, and time. Regulation can help by forcing boards to own the risk, and in Italy that pressure is rising through NIS2 implementation and the broader push for structured reporting and readiness.

Still, compliance will never substitute for competence. The operational question is whether leadership will fund fundamentals that are boring but decisive: asset inventory, credential hygiene, segmented networks, tested backups, and incident drills that are practiced, not performed. The financial argument is not theoretical either; the IBM cost of a data breach report keeps showing how quickly containment delays translate into direct and indirect loss.

A serious response also requires more honesty about the human system. The most capable defenders will not stay in roles where stress is normalized and autonomy is theater. The most diligent employees will stop reporting early signals if every disclosure becomes a personal risk. This is where ACN can set expectations and publish guidance, but where companies must do the hard part: build cultures where the first report is rewarded, not penalized.

Italy does not need a new buzzword to fix a 10% anomaly. It needs organizations that match their public values with daily reality, and leaders willing to trade short-term comfort for measurable resilience. That work is not glamorous, but it is the only way the number stops being a warning.