The end of security as we knew it: what Claude Code Security really means

The announcement that shook the market

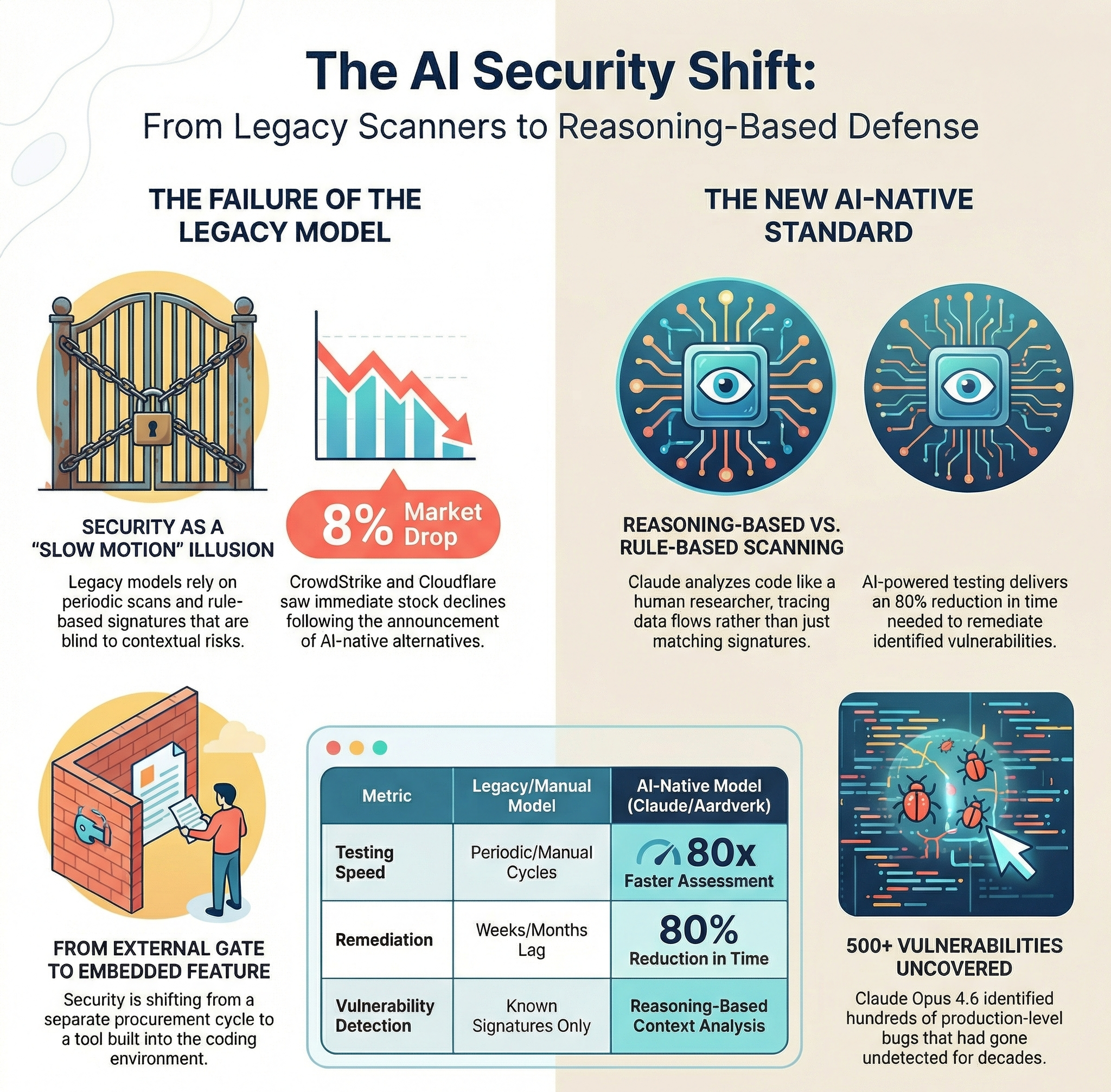

On February 19, 2026, Anthropic unveiled Claude Code Security, a new capability integrated into its Claude Code platform, and the cybersecurity industry felt the tremor almost immediately. CrowdStrike saw its stock drop nearly 8% in the hours following the announcement, while Cloudflare shed just over 8%. These are not modest corrections; they signal a market recalibration, a repricing of assumptions that had underpinned the sector for years. Whether or not AI-native security tools will actually replace traditional vendors remains an open question, but the market voted swiftly, and it voted with conviction.

The drop was not driven by panic or speculation alone. Investors and analysts grasped the structural implication behind the launch: a reasoning-based security scanner, built directly into a developer workflow tool used by thousands of engineering teams worldwide, could compress the need for dedicated third-party security products in ways that have no real historical precedent. For the first time, frontier-level security analysis was being packaged not as a standalone enterprise product requiring dedicated procurement, integration, and training cycles, but as a feature embedded in the environment where code is actually written.

How Claude Code Security actually works

What distinguishes Claude Code Security from conventional scanning tools is its departure from rule-based pattern recognition. Traditional static analysis tools work by matching code against a catalogue of known vulnerability signatures. They are fast, consistent, and by definition blind to anything outside their rulebook. Claude Code Security takes a fundamentally different approach: it reads a codebase the way a senior security researcher would, understanding how individual components interact, tracing data flows across the application, and flagging vulnerabilities that emerge from context rather than from a known fingerprint.

Each finding goes through what Anthropic calls a multi-stage verification process, designed to filter out false positives before results ever reach a human analyst. Identified vulnerabilities are assigned severity ratings to help teams prioritize, and each issue also carries a confidence score, an honest acknowledgment that even reasoning-based systems can be uncertain. Critically, nothing in the system applies changes automatically. Patches are suggested, reviewed on a dedicated dashboard, and approved by developers, keeping a human firmly in the loop. This human-in-the-loop design is not a limitation but a deliberate principle: the tool is built to augment decision-making, not replace it.

This is not theoretical capability. Using Claude Opus 4.6, Anthropic’s internal security team found over 500 vulnerabilities in production open-source codebases, bugs that had gone undetected for decades despite years of expert review. The tool is currently available in limited research preview for Enterprise and Team customers, with an expedited, complimentary access path for teams managing open-source repositories.

The structural obsolescence of the old model

The market reaction made headlines, but the deeper story is structural. For years, enterprise security has operated on a model essentially designed for a slower world: periodic scans scheduled weeks apart, vulnerability backlogs stretching into hundreds of unresolved items, and exhausting cross-functional negotiations over which risks deserved immediate attention and which could be deferred. The irony is that these practices never truly managed risk; they managed the illusion of managing risk. Security teams spent enormous energy producing reports that documented exposure without meaningfully reducing it.

A World Economic Forum study from 2025 found that 88% of security teams reported significant time savings through AI-assisted operations. AI-powered penetration testing now runs approximately 80 times faster than traditional manual assessments, with an 80% reduction in remediation time for identified vulnerabilities. These are not incremental improvements; they represent a fundamental shift in what security teams can realistically accomplish per unit of time, and the gap between organizations that have embraced this shift and those that have not is widening every quarter.

The old model made sense when threat actors also operated slowly, when the window between vulnerability disclosure and active exploitation was measured in months rather than hours. That window has collapsed. Attackers now leverage the same AI tools that defenders are only beginning to adopt, automating reconnaissance, payload generation, and lateral movement at a speed that periodic scanning simply cannot match. The asymmetry has become untenable, and the organizations still relying on legacy processes are not managing their exposure; they are simply choosing not to look.

A competitive landscape in motion

Anthropic is not operating in isolation. The AI-powered security space is becoming crowded with credible players, each approaching the problem from a different angle. OpenAI began beta testing a tool called Aardvark in late 2025, an autonomous security researcher built on GPT-5, signaling that the two leading AI labs are now in direct competition in the security domain. Meanwhile, the broader market for AI-native security tools is expanding rapidly, with 97% of organizations reportedly considering AI adoption in penetration testing workflows.

Traditional vendors are not standing still. CrowdStrike has accelerated investment in its Charlotte AI assistant, integrating generative capabilities into its Falcon platform. Palo Alto Networks has expanded its Cortex XSIAM suite with AI-driven threat detection, while Fortinet has deepened its use of machine learning across its Security Fabric. Yet these efforts are largely retrofits, AI capabilities layered on top of architectures designed for a pre-AI era, rather than ground-up rethinks of the security model itself.

This convergence of capability and demand is reshaping how security is purchased, staffed, and integrated into development pipelines. The traditional model of security as an external validation gate, a checkpoint imposed on engineering at the end of a release cycle, is giving way to something more continuous and embedded. Claude Code Security, deployed directly inside a developer’s coding environment, represents a logical endpoint of this shift: security that travels with the code from the moment it is written, rather than arriving after the fact to report on the damage.

What it does not cover: runtime behavior

It is worth noting, however, that the current version does not test runtime behavior. It cannot send requests through an API stack, validate how authentication middleware chains under real conditions, or confirm whether a finding is exploitable in a live environment. Those classes of vulnerabilities, the ones most likely to appear in actual incident reports, only manifest at runtime. A mature AppSec program will therefore need to instrument both code-level reasoning and runtime validation in parallel, not treat one as a substitute for the other.

A reset, not an extinction

None of this means that the expertise, judgment, and creativity of skilled security professionals becomes obsolete. What it means is that the definition of what skilled looks like is shifting. The analyst who spent most of their working day triaging alert queues and writing remediation tickets is looking at a radically different role profile than the one who knows how to configure, interrogate, and challenge an AI-assisted security system effectively. These are not lesser skills, and the transition may lead to work that is both more demanding and more genuinely impactful.

What is ending is the institutional inertia that allowed security to remain expensive, slow, and operationally noisy without accountability. The cybersecurity sector is entering a transformation phase: faster identification of real vulnerabilities, reduced operational noise, tighter integration with development workflows, and transparent confidence scoring are not aspirations for a distant future. They are capabilities available, in preview, today. The tools now emerging do not diminish domain expertise; they amplify it, provided that expertise is applied to the right problems. The challenge is identifying which problems those are before the competitive landscape makes that choice for you.